Interview with Dounia Bouzidi and Joseph Rozenkopf for Que restera-t-il?

Interview by Sandrine Allen

Article reviewed by Léa Mora

Far from being timeless, a work of art is rooted in the historical and social context in which it was created. From the end of the 18th century, philosophers such as Hegel and Friedrich Schlegel, influenced by German Romanticism, broke with the aesthetic conventions of the past and the tradition that saw art as a mere functional or decorative object. They insisted on the need to rehabilitate sensitivity, imagination and the presence of intuition, asserting that art expresses our vision of the world and represents a way of existing in time. From this perspective, artworks are not mere relics of the past, but living experiences that speak to us and bear witness.

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

It is in this spirit that the exhibition Que restera-t-il, presented at Livart during winter 2025, offers a sensitive reflection on memory, disappearance and the persistence of forms. In this way, each work is an encounter and becomes a living trace, a gesture that questions what we leave behind… and what continues, despite everything, to connect us.

We spoke to the two curators and friends, Dounia Bouzidi and Joseph Rozenkopf, to find out how they experienced their collaboration and the reflections they developed around this exhibition, which took place as part of the second edition of the Forum arts visuels émergents – FAVE 2025.

Can you tell me about your collaboration and how your backgrounds influenced this project?

Joseph: It was a real challenge because we’re friends first and foremost. Sometimes, when we saw each other, we didn’t know whether we were seeing each other as commissioners or as friends. Discussions soon overlapped. It’s a project that’s a bit in keeping with our friendship, because we knew we worked well together, but this project was more specific.

Dounia : We already had a strong interest in culture, and often went to exhibitions together. It was an activity we shared a lot and it gave us a common inspiration. I think that after the video and this professional work, the prospect of putting on an exhibition really catalyzed our collaboration.

We soon realized that our aesthetic interests were shared. There was a real convergence in what we liked, and even if our understanding and backgrounds were different, we still had a great aesthetic connivance.

I think we were already convinced that we were going to do a project together at some point, and now we’ve finally had the chance to develop it.

Thanks to their approaches, built on parallel fields of study and different horizons, they have adopted a singular and complementary reading of art.

Dounia: What’s interesting about the way we work is that we come from two slightly different worlds. Joseph has a very material approach to artworks, he’s interested in the way they’re made, the materials. I’m more focused on concept, discourse and aesthetic precision.

For me, what’s interesting about our collaboration is the juxtaposition of these two worlds. Joseph has a very good eye for materials. I come afterwards, to create an interpretative discourse on what we’re building.

I think that’s the strength of our partnership.

How did you approach your first role as curator in selecting works and artists?

Dounia: When we choose works and artists and decide to bring them together, it’s we who create the common thread running through the exhibition. So for us, there was also a desire to leave a trace through this common thread.

The notion of transmission is very present in the exhibition. With this in mind, we wanted to address the question of what artists leave us, the public and the world. With whom do they engage in dialogue through their work?

It’s also a question that touches on what we, as curators, want to convey through our own interpretation of the works.

Ultimately, yes, it’s about leaving a trace, but it’s also about questioning what remains in concrete terms.

The exhibition, which brings together eight artists, was intended to question notions of leftovers in the materiality of the works, while acknowledging the political considerations dear to the artists.

Both cultural workers, Dounia and Joseph were keen to put forward their own reflections on the place of Montreal artists in Quebec’s institutional and cultural landscape.

Dounia : Je pense que la notion de trace sera peut-être plus intéressante à aborder du côté de l’émergence. Il y avait cette volonté peut-être un peu égocentrique, mais aussi née d’un intérêt de notre part en tant que commissaires nous aussi dans nos débuts, de montrer les créations d’artistes émergents, de montrer qu’eux aussi peuvent laisser une trace dans le collectif, dans ce qui fait l’art actuellement.

So how do you see emerging artists bringing a new dynamic to contemporary art?

What’s going on in the world, the concerns we all share, I think our artists feel them too. It’s not just about showing that we’re part of the emerging art scene and that we can do things. The idea was also to show what emerging art can bring to the wider world, as something new, as a new way of understanding the world.

The institutional framework of contemporary art presents artists with a series of choices to reconcile creation and remuneration. Faced with these dilemmas, where “money” and ‘art’ collide, several artists seek to challenge the romantic image of the “bohemian” artist and creation free of contractual constraints.

Textile artist Sam Meech tackles this issue with his performative work 8 hours labor, completed at the exhibition’s opening night last winter 2025.

How did you approach the theme of the status of emerging artists in your exhibition?

Joseph: Whether in the display or in the way they were made, the works were by rather DIY artists.

Do it Yourself is a movement associated with an approach aimed at autonomous production. The term refers to activities that seek to create and repair objects as a counterpoint to conventional expertise. This includes the manufacture of everyday objects, as well as technological and artistic ones.

We tried to avoid having the works laid out somewhat randomly. We wanted to enable visitors to understand how they were made.

I think everything is quite visible. For example, at the beginning of the exhibition with Sam’s work, you don’t just see the end result, but you make the process visible. The same goes for Poline’s work, where you can see the leftover thread on the back. We really wanted to make the creative process visible, and put it forward.

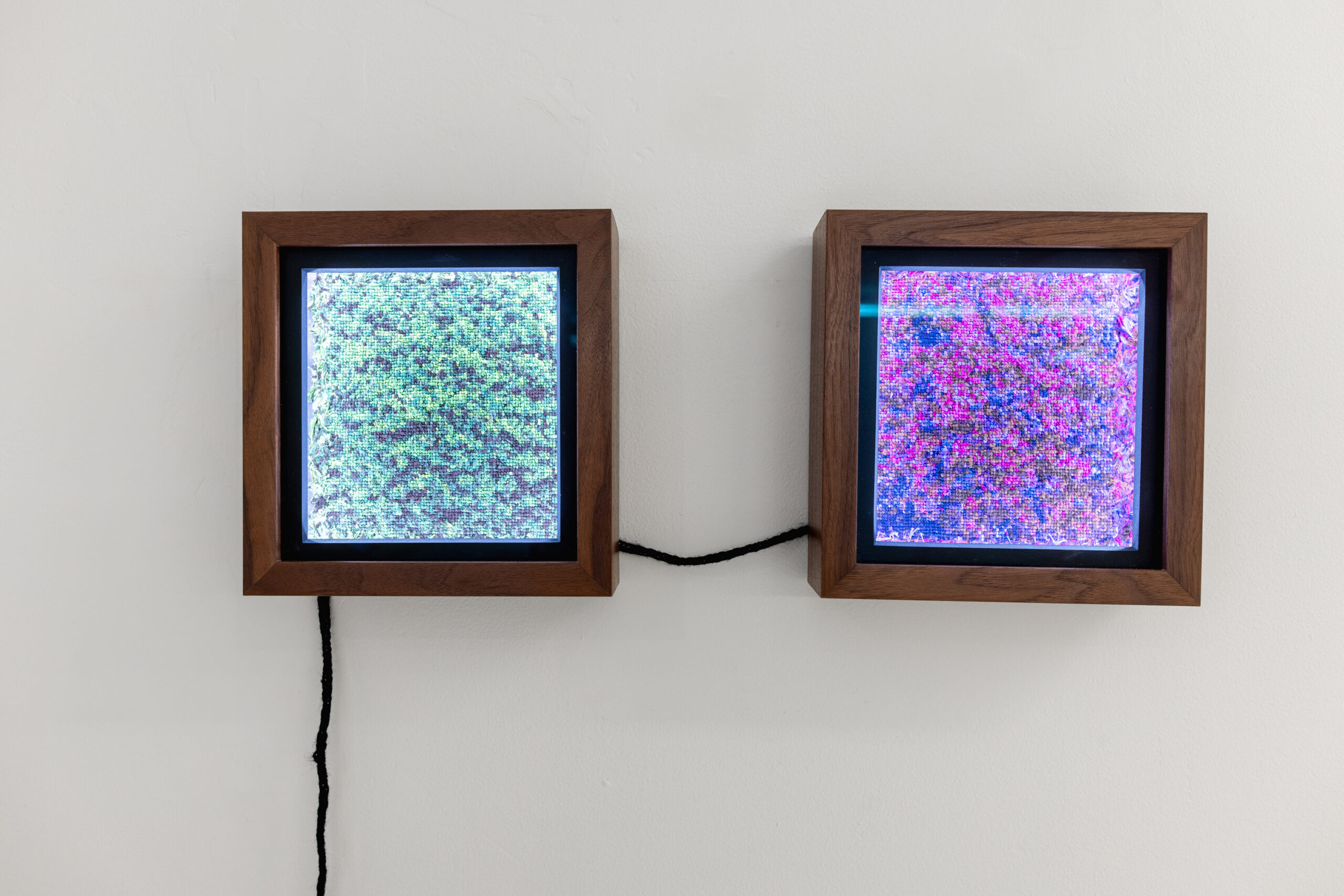

Crédit photo : Katya Konioukhova

With the parallel of transmission, the exhibition also focuses on the treatment of materials and the techniques used. Even if this is not the main focus of each artist’s work, all of them take an inordinate amount of time to make. There’s no such thing as a quick work.

This is often the case with textile artists, but also sometimes with painting. That’s why we’ve also chosen paintings that are a little out of the ordinary, either very large formats, or Charlotte’s epoxies.

I think that this notion of work, hard work and repetition is very present, particularly in Sofia’s work. There’s a succession in her creative process that also reflects the time it takes to complete the final work.

How can we perceive the creative work that remains invisible, sometimes right up to the final result?

Dounia: Yes, there really is an enormous amount of invisible work involved in production, and it depends very much on the medium used. For example, in Sam’s work, it’s quite literal: he works for eight hours, and the work itself is this eight-hour labor. In the other works, there’s also a lot of time that isn’t visible or accounted for. I don’t know exactly how much time Sofia put into her work, but it must be equivalent, if not more, to what Marwan invested in his embroidery. These embroideries are extremely time-consuming. I can’t remember the exact number of hours, but it’s in the hundreds for each piece.

We saw him, because these are people we know very well. We saw him work for months on his pieces. It’s not something he did from morning to night, but we know it’s a huge part of his life.

Joseph: Yes, exactly! There’s an aspect where you work so invisibly that it’s anchored in the everyday life of artists.

In other words, you can be chatting with someone while working on an embroidery, even if it’s hard to judge. The little time you have becomes your creative time, especially when you don’t have the means to live solely from your art. There’s this questioning about when the artist’s working time stops and your other work begins, sometimes as a student or whatever.

Can the notion of trace also refer to the artist himself and his place within his network? Is this dimension present in the works?

Joseph: Absolutely, all the works have this relationship to the self. It’s a subject we’ve begun to explore, even if it’s perhaps a little obvious. In fact, we started with this micro-subject before opening up our concept to something more social.

Every artist leaves a part of himself in his work, even if some works show this more explicitly than others.

I think it’s part of the transmission and representation of the self, a form of outward-looking personal expression. It’s quite important, especially in the artistic gesture of certain creators.

In Poline’s work, for example, we find a common heritage that makes for a very interesting sense. She works with Syrian tablecloths that belong to her family. This information would have to be verified to be exact, but it seems to me that these are pieces that have been passed down to her.

From this heritage, she creates an imaginary conversation with the people around her who are dear to her. Her work is very intimate and personal.

It’s a bit similar, because all the people depicted in his works are family and friends. Each work captures moments in life. Poline is also a photographer, so her artistic practice retains a link with photography, but here she takes the liberty of integrating collage into her creations. The titles of the works always refer to the identity of the people depicted, even if this identification can be subtle. It’s not always as obvious as a direct visual identification, as is the case in other works where the desire to exist, or to leave a trace, is more obvious.

Do you have any final thoughts on your exhibition Que restera-t-il?

Dounia: For me, the simple fact that people remembered and came to see our exhibition is already a success. I don’t think either Joseph or I are very keen on the exhibition sending out a precise or specific message. In fact, it’s not something that really belongs to us.

What counts is that the people who come, whether friends or family, support the project. And as long as this dynamic continues, that’s what’s most important.

While you’re preparing the exhibition, and even once it’s open, there’s a lot of thinking and work to do. But it’s not really up to us to receive feedback directly; often, it’s the venue that collects it.

To find out more…